You are here: Material Science/Chapter 1/Polymers

So Many Polymers

If you look around at the materials wherever you are right now, chances are that many of them aren’t any of the materials we’ve talked about. So here we will introduce something that will explain the basics of many, many materials around you, including many natural materials – wood, cotton, leather, silk. But also proteins, enzymes and starches. These materials that I’ve listed can all be found in nature. But advances in technologies have meant that we can create these materials synthetically, too. And what materials came out of this? Plastics, rubbers, and fiber materials. You’ll agree that this is a very important group of materials in our daily lives. Here, we discuss polymers.

Hydrocarbons

But let’s back up a bit and talk about hydrocarbons, which is sort of the basis of polymers. Indeed, many naturally occurring materials (or organic materials) are comprised of hydrocarbons, which as you may have guessed, are made of hydrogen and carbon. The bonds between hydrogen and carbon are covalent – electrons are shared, so that the atoms involved can fill their outer shells. Carbon atoms have a total of four valence electrons that may participate in bonding with other atoms. Hydrogen atoms only have one atom to share.

Single Bond

A single covalent bond occurs when a pair of electrons (two) are shared. Let’s talk about when carbon bonds to hydrogen. In this case, the hydrogen atom shares an electron with the carbon atom, and the carbon atom also shares an electron, so effectively each atom has gained a single electron. At this point, the hydrogen atom is good to go; it doesn’t have anymore electrons to share and will not bond to any other atoms. But the carbon atom still has another three electrons – what to do with these? It could bond with three other hydrogen atoms. That is definitely an option – the carbon atom forming a single bond with four hydrogen atoms.

Double Bond & Triple Bonds

Of course, carbon can also bond to carbon, with a single covalent bond. This leaves 3 additional valence electrons available for bonding. Each carbon atom can then bond to three hydrogen atoms, if it chooses. Or it can also double bond with another carbon atom. Two carbons atoms could each contribute two electrons each, or so that a total of four electrons are involved – a double bond. If the carbon atom is double-bonded to another carbon atom, and is also bonded to a hydrogen atom, then it still has a free electron. And so, you can have bonding with three electrons each from the carbon atoms – for a triple bond. With a triple bond, the carbon atoms only have a single free electron to share, so they could only bond with a single hydrogen each, and all the carbon’s atom valence electrons would be used up. Saturated & Unsaturated

Saturated & Unsaturated

Here’s where familiar terms of saturated and unsaturated come in (no doubt you’ve heard of saturated and unsaturated fats). Saturated simply means that, with a single carbon atom, all the bonding it does are single bonds, and so it has bonded with the maximum number of atoms – four. If there are any double or triple bonds, then the hydrocarbon is unsaturated, as it would be bonded to less than four hydrogens atoms.

Simple Hydrocarbons

Simple hydrocarbons, in the paraffin family for instance (yes, like what candles are made out of), as you know, have pretty low melting points. Hold a lighter flame over a candle and it will start to drip. What is actually happening when the wax is turning into a liquid? Well, the bonds within the molecule itself, between the carbon and hydrogen, are strong – they’re of the covalent variety, which means that electrons are shared between atoms. Those are strong bonds, strong enough that they will not break apart due to the heat that the flame is providing. But the bonding between the molecules is weak – it’s only weak hydrogen bonding and some van der Waals bonds. You don’t want van der Waals bonding when the going gets tough. Those break apart pretty easily when the molecules start to writhe about and shake when heated, and when those weak bonds between the molecules break, the wax flows.

Here are some very simple hydrocarbons belonging to the paraffin family:

You can see a pattern with the above molecules. Start with methane, and add a carbon and another two hydrogens and you have ethane. Do the same again, and you’ve made propane. This continues:

You can see a pattern with the above molecules. Start with methane, and add a carbon and another two hydrogens and you have ethane. Do the same again, and you’ve made propane. This continues:

- Butane: C4H10

- Pentane C5H12

- Hexane C6H14

Now you know a bit about hydrocarbons. And we still need to talk about polymers. Well, polymers also are predominantly composed of hydrogen and carbon, which is why we discussed hydrocarbon.

Just a note about the size of hydrocarbons versus polymers. Take propane – C3H8 – for example. 3 carbons bonded with 8 hydrogens, all single bonds. This molecule seems like it is a reasonable size. It has a total of 11 atoms. But polymers are massive compared to a molecule of something like propane. This is because each molecule is very long, as we will see. They are termed macromolecules.

Carbon Chain Polymers

Most commonly, polymers are long molecules that have a backbone of carbon atoms. There are other structures, but for now, we’ll just talk about carbon chain polymers. Each carbon atom bonds covalently to the carbon atom next to it, and so on, many, many times. Each carbon in the chain (except for the two end ones) have two free electrons that can particulate in further bonding. Double bonds are a possibility as well – it all depends on what polymer we’re talking about.

Repeat Units, Homopolymers & Copolymers

To make things easier to draw and discuss, material scientists have come up with what is called the repeat unit – just small sections of the polymer that are repeated all the way down the chain. Kind of like a Lego sculpture – the sculpture is all made from the same lego pieces, which are analogous to the repeat units. This is not to be confused with the monomer – the small molecule that the polymer is created from. You see, each polymer chain forms by taking a single monomer and growing it by tacking on additional monomer units at the end. What we’re left is a chain at the end of this process (we can talk about this process in a minute). So whereas the repeat unit can be thought of almost as an easy classification system of the long polymer by dividing the chain into smaller repeating pieces, the monomer is the actual repeated small molecule. So, they are used interchangeably but actually don’t necessarily mean the same thing. If the repeating units of a polymer are all the same type, then the polymer is termed a homopolymer. If not, if there are more than just one type of repeat unit in the polymer, then it’s a copolymer.

Let take the polymer polyethylene to illustrate a couple of points here. You’ve probably heard of polyethylene, or it’s abbreviation, PE. It is extraordinarily common. Plastic bags, plastic films, plastic bottles, it’s everywhere, as global production is estimated to be around 80 million tonnes (1 tonne = 1000 kg, or just over 2200 pounds). To try to put that into perspective, the empire state building weighs about 330,000 tonnes. So the equivalent mass of 240 empire state buildings worth of polyethylene is produced every year.

PE is basically just a long hydrocarbon chain. The repeat unit of polyethylene is C2H4:

The n denotes that this is just the repeat unit, and that the actual polymer molecule is n (a large number) of these attached together. The monomer is ethylene.

Polymerization

How do we form a polymer? I’ll be very, very brief. Take a hydrocarbon – something like ethylene, shown above, (which is actually a gas at room temperature) will do. Let’s react that gas in certain conditions, and it will transform into a solid polymer – polyethylene now. What are those special conditions we need? Basically, we need a reaction of the initial gas with a initiator (catalyst) and the ethylene molecule. This catalyst will actually break the initial double bond of the ethylene molecule, leaving the carbon atom at the end with a free electron to share. The chain grows as more monomer units add on the end.

A side note here about the convention for drawing polymers. Whenever I draw a carbon chain, I’ve shown it to be straight across – 180 degrees. In reality, the carbon chain zig zags at something around 110 degrees instead. Like so:

In the polymerization process, you end up with a lot of molecular chains. As I just mentioned, these chains zig zag around – the bond angle is about 110 degrees. Depending on how the bonds happen, the molecular chain can make quite a few crazy turns and has a number of kinks and bends. It’s anything but perfectly straight. The end result of each chain would look something like you trying to draw a straight line in the middle of an earthquake. A piece of something like PVC piping, which is made of polymers, isn’t just one of these molecules. There are many, many of these molecular chains, each with it’s own particular brand of crazy kinks and bends. You can imagine, then, just how tangled up these chains get. It would be like jumbling up a massive number of headphones. But this mess of entanglement and general randomness results in some really interesting properties. It’s part of the reason why rubber materials, like an elastic band (made of a natural rubber, usually), can be stretched so extensively without breaking. When you stretch the band, you are basically straightening out all those kinks in the long chains that are extremely jumbled.

There’s some properties, both mechanical and thermal, that are also affected by the bonding within the chain molecule – particularly whether there are double bonds present. Double bonds are very rigid – they are excellent at resisting rotation. Just think of nailing two piece of wood together. With a single nail, it is easy to rotate the pieces of wood. Add a second nail and the rotation is prevented. Same with double and single bonding. The part of the molecule that contains the double bond won’t rotate much. If double bonds are present in the molecule (and this depends on the polymer) the mechanical properties will be affected for sure.

A note about the synthesizing process: growing the polymer doesn’t result in a bunch of chains that are exactly the same length (and thus the same weight). The polymerization process isn’t that perfect. In fact, there is a decent range of molecular size in polymers, which are scattered in roughly a normal distribution. A few molecular chains are very, very small. There are some though that are really quite large. The majority fall somewhere in the middle.

Linear Polymers

So far, I’ve given the impression that all polymers are just made up of a bunch of individual molecular chains. That’s true for what are know as linear polymers. In linear polymers, the repeat units are just joined end to end in a straight line. The chains are flexible and a tangled mess, like a pot of spaghetti, which is actually a pretty good analogy. The molecules themselves are fairly strong, since all the atoms within the molecule are covalently bonded. There is also hydrogen bonding and van der Waals bonded between the chains. Back to the spaghetti analogy: if you pick up a clump of spaghetti, some of the noodles will stick together – this is representative of the secondary bonding between the linear chains. The noodles are easy to pull apart; the bonds are weak. The noodles themselves, however, which represent the molecular chains, are significantly stronger; the noodles are tougher to break.

Branched, Crosslinked, and Network Polymers

There are other structures than just linear. There is also branched. In a branched structure, the main linear chains are interconnected by shorter chains. These chains are still part of the main molecule. These bonds are covalent, not secondary, so they’re relatively strong. Because these side branches space out the main chains, the packing is reduced, meaning that these polymers tend to be less dense. What other types could we have? In addition to linear and branched, there is cross linked. Cross linked polymers are similar to branched but there are no side branches. Instead, the linear chains are all joined together at random positions by covalent bonds. Many rubbers are cross linked. Anymore polymer structure types? One more that we’ll talk about! There are network polymers too. Network polymers are basically highly cross linked polymers. Each molecule covalently bonds to three or more other molecules to form a 3D type network. Usually, no polymer has 100% one type of structure. A linear polymer may have some cross linking occurring, for example.

Head to Head & Head to Tail Configurations

Now that we’ve talked about the molecular structure of polymers, we can talk about the different molecular configurations. So far we’ve assumed that the repeat unit attaches end over end exactly the same way. But it doesn’t have to happen like this. For example, let’s talk PVC, poly vinyl chloride, which is commonly used to make piping for sewage and drainage systems. The repeat unit has two carbon atoms, three hydrogens, and one chlorine in the bottom right corner. The first configuration has the chlorine alternating between hydrogen atoms: this configuration is the termed head-to-tail.

So there is also head-to-head, which is less common. In this configuration, the two chlorines are neighbours; they are adjacent. This leaves two hydrogens atoms adjacent, then back to two chlorines, and so on. This configuration isn’t nearly as common, because often those two chlorines will repel each other (like two magnets of the same polarity).

Note that in this example we’re using Cl (this example is PVC), but this could be many different atoms or molecules. Usually, this is denoted by calling it an ‘R’ group. So instead of Cl, there would be an ‘R’ in the image, to indicate that it could be a variety of atoms or molecules.

Isomers

Isomerism is when a compound of the same composition (i.e., same number of atoms) has a slightly different structure. The butane hydrocarbon, for example, has a composition of C6H14. It has a couple different ways that these atoms can structure themselves (two isomers). One isomer is butane, and another is isobutane. They both have the same number of carbon atoms (6), the same number of hydrogen atoms (14), but the bonding that occurs between the atoms is slightly different.

To further complicate things, there are two different subclasses of isomers:

- (1) Stereoisomerism;

- (2) Geometrical isomerism.

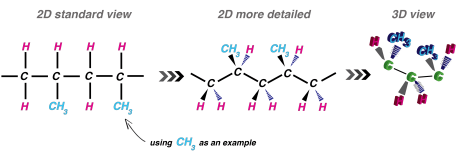

Before we go on: we need more detailed visualizations. Look at the figure below. These are all the same polymer. The standard 2D visualization is shown far left. The middle image (more detailed 2D) shows the angled carbon backbone. By the way, you can see that this is a head-to-tail configuration. Moving along the chain, you can see that the CH3 groups bond on every other carbon atom. The 2D also has ‘wedges’ that branch off the carbon chain. The solid wedges are coming out of the screen towards you. The stripped wedges are going into the screen, away from you. The 3D view tries to show this a bit better. You can see that the CH3 groups, in this case, are on opposite sides of the chain.

Again, remember that CH3 is just being used as an example. This could easily be a different atom or molecule.

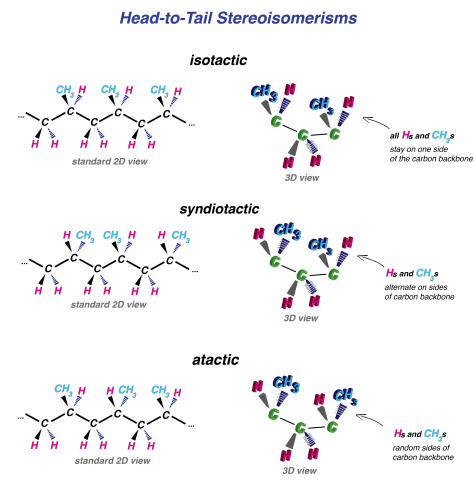

(1) Stereoisomerism only occurs with the head-to-tail configuration. That’s a key point.

There are 3 types:

- The R group (CH3 in this case) can either be entirely on one side of the chain (all going into the page or all coming out) – in which case this is an isotactic configuration.

- OR, the R group can be on alternating sides of the chain – which is called a syndiotactic configuration

- Finally, the R group can be randomly on either side: the atactic configuration.

You might be thinking: what’s preventing a R groups from rotating around that carbon chain and changing configuration? Why can’t a isotactic become an atactic? Well, it can’t, for the simple reason that the bonds would have to be severed first, completely. There’s too much bonding going on for the atoms to swing freely around the carbon atom.

(2) Geometrical isomerism . This occurs with repeat units that have a double bond between two carbons atoms, and whether or not the side group is on the same side as the hydrogen atom or not. If the side group is on the same side of the hydrogen atom, the structure is called a cis structure. For the side group which resides on the opposite side of the hydrogen group, it is a trans structure.

Trans, like across. As in transcontinental, or transatlantic. Cis, latin for “on this side.”

Thermoplastics and Thermosets

I’d say that the most frequent classification of plastics that comes in engineering is whether the polymer is a thermoplastic or a thermoset. As you might have guessed based on the first part of the terms, thermo, this is a classification that had to do with temperature – specifically, how the polymer reacts to elevating temperatures. It may sound like an arbitrary classification system, but it’s pretty useful. You’d want to know whether a plastic is a thermoplastic or thermoset before putting it in the dishwasher, for example. Why, exactly?

Put briefly, a thermoplastic melts. A thermoset does not: it will resist melting and eventually burn at excessive temperatures. A thermoplastic melts because it has a linear or branched structure, and secondary bonding between the chains is easily severed by increased molecular motion provided by the introduction of thermal energy. The thermoplastic gets heated, the molecules wiggle and break free, the molecules are free to move around, and the plastic has melted. Once the thermoplastic polymer cools, those secondary bonds will reform between the molecules, and it will re-harden into a new shape. This process is repeatable. Melt, harden, melt; harden. This type of plastic might be useful then for using in applications where the component would be recycled afterwards – like a water bottle – so that the plastic can be melted down and reused.

Thermoplastic is like chocolate, or ice, or molten metal. Once it solidifies, you can heat it up to make it liquid, and then let it solidify again.

Thermosets are set in their ways. They pick a shape and stick to it; there won’t be any melting from them. This is because they have a network structure, or are highly crosslinked. Those bonds between the molecules are all covalent, and they aren’t going to break easily. The bonds resist the vibrations caused by heating, and the plastic doesn’t even soften. It just burns. Something that is desirable about thermosets is that they are usually harder and stronger than thermoplastics and are more rigid. So the use of a thermoplastic or thermoset really depends on the application (as with any material, really).

Copolymers Continued

You know how we briefly discussed copolymers – polymers that comprised of more than just one unique repeat unit. Material scientists are always messing around with synthesizing different polymers to see what kinds of better material properties we can get. Or maybe they’re looking for polymers that are easier to create and cheaper to make.

In any case, there are a few different ways to organize the repeat units. A polymer consisting of the same repeat unit throughout is a homopolymer. But say we have two different types of repeat units, A and B. You could so one after the other – like A-B-A-B – this is called alternating. Or you could randomly join the repeat units – A-B-B-A-B-A-A-A – something like that; that’s called a random copolymer. Or you could do chunks of each – AAABBBAAA – that’s called block. Or finally, you could have linear chains of all type A and all type B intersect each other – that’s a graft copolymer.

Polymers and Crystallization

I would like to talk (briefly) about crystals and crystallinity and how these concepts that we’ve talked about extensively for metals, how they relate to polymers. Polymers can actually exist in a crystalline state, which seems a bit strange, because we’ve mostly talked about how polymers look like jumbled up spaghetti – and we know that crystals have ordered, very tidy, very neat, structures. When we think of a crystal structure of a metal or ceramic, we think at the atomic level. But with polymers, we need to think at the molecular level. All of those chains need to come together in an ordered way. As you can imagine, that’s a bit more difficult. It’s easier to neatly order a bunch of marbles inside a box (they just stack on top of each other) than neatly order spaghetti. Because of this complexity, rarely would you have a polymer material that is completely crystalline. It is much more common to have regions of crystallinity, scattered throughout the amorphous material (remember – amorphous means a non crystalline solid). Remember how much the chains twist and kink! Any chain misalignment will result in a non order, amorphous region.

Whereas metals are almost completely crystalline, polymers range from completely amorphous to about 95% crystalline – that’s a pretty big range. What’s interesting is that the density of the material can tell us to what extent it has been crystallized. It makes sense that a polymer that is highly crystalline will be denser than an equivalent polymer that is amorphous. It’s like packing clothes in a suitcase – if you fold your clothes so that the structure is neat and ordered (crystalline), then you make the most of the space. If you haphazardly throw your clothes in, you probably won’t get as many in (amorphous). How much crystallinity we end up with for a given polymer depends of how quickly the polymer cooled while it was forming, and what the chain configuration is. If you want a more highly crystalline structure you need to give the polymer sufficient time to cool – so that all those polymer chains can find a nice, ordered place to be. Just as it takes more time to neatly pack your suitcase. If you cool it quickly upon forming, the chains won’t have a chance to align and bond nicely to other chains. They’ll be frozen in place in whatever position they began in.

What else affects crystallinity? The complexity of the repeat unit plays a big role. If you’ve got a very complex repeat unit – and by complex I mean lots of bonds and atoms, in funky configurations – it’ll be tough for them to all for together, in an ordered way, when the polymer is forming. Some crystallinity will occur, but it definitely won’t be dominate. But take a very simple repeat unit – polyethylene is a good example, and it will crystallize pretty nicely, even if it was to be rapidly cooled. So some of this is out of our control: it depends on the repeat unit. This is partly why there’s such a big range in polymeric materials between totally amorphous and almost completely crystalline.

Structure is also important. Linear molecules will more easily align – there’s no awkward chains sticking out that prevents alignment. With branched structures , there are indeed branches sticking out awkwardly. This makes it difficult for branched polymers to crystallize. In fact, they may never, ever crystallize. They might be completely amorphous. And crosslinked and highly networked polymers are even more unlikely to crystallize. You can safely assume that those polymers are amorphous.

A summary on polymer crystallinity: polymers don’t crystallize like metals or ceramics do. Often, the molecules of polymers are big and complex, preventing ordered stacking and aligning. If the molecule is simple, or has a branched structure, then some crystallinity will occur – up to 95%! But more complex molecules, or polymers have branched, network, or crosslinked structures, will likely just be a jumbled mess – or amorphous, in engineering terms.

You just learned about polymers. Not too much, not little. Look around – if you see plastics, rubbers, wood, leather, silk (and I guarantee you that you’ll see some of those materials) you know a bit more about what those materials are actually made of, and maybe why they behave the way they do.

You are here: Material Science/Chapter 1/Polymers

<— Crystal Structure/Material Defects —>