You are here: Circuits/Chapter 1/Voltage

The force pushing the charge particles (electrons) along the conductor is voltage. That’s another thing that we need to discuss before Ohm’s law is introduced. What is required to truly explain it is a discussion about magnetism. You may find that a lot of these rather simple concepts are never actually taught in university level classes. Remembering now, I think that the professors assumed that this knowledge had been retained from studies during high school and earlier. But who can really remember what they learned in high school? And if it was taught, it was improperly, a dumbed down version for the students with some simplifications made – dangerous simplifications, that results in the more advanced courses such as digital and analog circuits building on a hazy understanding at best. I find it amusing and at the same time terrifying realizing that if the professor came up to me during one of those exams, when I was solving for some circuit design using differential equations, and asked me “What does this transistor that you’re solving for actually do?” I would have been totally lost. I have no idea. Maybe other students did indeed understand the concepts, but I somehow doubt this to be true.

1. Voltage and Electric Fields

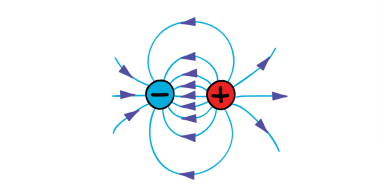

So the conductor is full of loose electrons, charged particles, that are ready to move and create current, if only they can be convinced to do so. And voltage is that skillful negotiator or intimidating persuader that forces the charge particles to flow. Voltage seems a bit abstract. Most of you probably know that it is the potential difference between two points. You can’t have the voltage of just one object or dot or item; it needs to be compared to something. Just like you can’t describe the height of a building without referencing the ground as the starting point. But there is more, and let’s talk really briefly about magnets, those bars of metal with north and south poles. If you sprinkle some iron powder in the presence of a magnetic field, the filings will line up in discrete places and align themselves. This field has lines of flux (the paths along which the field acts) and repels or attracts other magnets – everyone knows what happens when you try to push two north poles together. The above is a magnetic field and it is invisible. It also has an invisible relative called the electric field. It also has lines of flux and likes to attract and repel objects as well. However, it has carved out a separate identity for itself: voltage. The reader might be more familiar with another term for it; it is somewhat related static electricity, the kind that occurs when you rub a balloon on your head, or with a piece of wax that has been rubbed with wool cloth. Voltage is the cause for the attraction between two opposite charges. So it makes sense that the charge particles in a conductor – the electrons – only move when a voltage is applied. The voltage field which runs along the wire is forcing them to move, causing the flow of charged particles, or current. So voltage is responsible for the creation of current. With no voltage, there is no flow. This makes sense intuitively; a wire with no battery connected to it will have no current. You can handle it without fear of shock or violent death.

To get a bit more technical: voltage is really just a way to quantify the strength of the electric field, or the electric potential between two points. An electric field can be measured using volts over a certain distance. A very strong electric field would have a high volts per distance value. Another way to describe the same thing: if you have high voltage over a very short distance, the electric field strength is strong. You may be wondering what the difference is between an electric field and a magnetic field. An electric field (and therefore voltage) surrounds two electric charges separated by some distance. A magnetic field surrounds two opposite poles separated by some distance. So voltage and magnetism are like siblings or life long friends. They know a lot of the same people and run in the same social circles.

The full definition that you will likely see the most often: voltage is the electric potential energy per unit charge. What does that gibberish mean? Imagine two points. Let’s say that it’s Los Angeles and NYC. They are located some distance apart. Say that these points are in the presence of an electric field. Now, your job is to move a charged particle. This charge particle is called the test charge. How much effort do you need to put into this job; how hard do you have to push to get that charge (let’s call him Jim) from A to B? This is exactly what voltage is: the total energy required to move Jim along that path. We need to factor in the magnitude of that electrical charge, in order to normalize everything. If you used a different magnitude test charge, a bigger Jim, you wouldn’t end up with the same amount of energy required to move that charge, right? That doesn’t seem fair or like a good way to measure the potential energy in the field. So take the total energy required to move that test charge as above and divide it by the magnitude of the charge. That is why voltage has the units electric potential energy per unit charge, where per means divided by. To reiterate: voltage is the energy required to push a charged particle in an electric field. That is why it creates current in a wire – it pushes those electrons which are already packed into the wire and creates electron flow.

2. It’s All About Potential

Keep in mind that the voltage has to be measured between two points in order to make any sense at all. Although, professors and textbooks will often talk about the voltage of a particular node or point in a circuit, which seems wrong right? But they are most likely referring to the voltage at that point compared to 0 volts at the ground of the circuit. So they aren’t explicity saying, What is the voltage between this node and ground? A shortcut that may cause some initial confusion. To understand the idea of measuring it between two points, think of a baseball that is suspended at some height above you, and someone will give you $100 if they can drop it on your head (for some sort of medical experiment regarding the impact of baseballs and the human skull). What is the logical question here? You are going to be pretty darn interested in the height at which that baseball is going to drop, or the difference in height between the baseball and your head. If it is 3 centimeters you might be a willing participant in the experiment. If the height difference is 1km, you will likely politely decline and explain your pre-existing plans to catch a movie on that particular night. You need to know how far that baseball is going to drop. Your life may depend on it. Likewise, we need to know how far we are moving that charge particle in the presence of the electric field to determine how much energy is involved. So voltage is always expressed between two points.

You are here: Circuits/Chapter 1/Voltage

Previous Topic: Current

Next Topic: Current Part II